in April 2020, not a soul on the planet would describe our situation as normal. It’s anything but. The world is under siege by a virulent pathogen. We’re all “social distancing” and “sheltering in place,” that is, hunkered down at home for weeks on end, leaving only if our work is deemed “essential,” or if we’ve run out of food. Every state in the union has declared a State of Emergency, the first time that’s ever happened.

As a result of this contagion, our economy has taken a mighty punch to the gut. Seventeen million people have applied for unemployment in the recent three-week span and Congress just passed a third relief bill, worth more than $2 trillion — the biggest such effort ever — and leaders already acknowledge they’ll need to do much more. The stock market sank nearly 30% in little more than a month. The International Monetary Fund predicts that the coronavirus pandemic is likely to trigger the worst recession since the Great Depression.

It’s horrendous beyond words, but even prior to this year, the world was spinning a bit wobbly on its axis. Over the past few decades, Americans have become more partisan politically, and thanks to cable news and social media, debate on issues large and small is more acrimonious. The ranks of billionaires, and the extreme wealth they hold collectively, has grown steadily over the years, yet on any given night a half-million Americans sleep on the streets. A couple years ago 47,000 Americans died from an overdose of opioid drugs and, tragically, even more than that took their own lives — among them, my dear brother-in-law. As a recent New York Times editorial put it, “over the past half century, the fabric of American democracy has been stretched thin.” Topping the crises we faced prior to COVID-19 is climate change. Even as the current administration dials back environmental regulations and lends continued support to fossil-fuel industries, the giant investment firm JP Morgan warned in a January 2020 report, “We cannot rule out catastrophic outcomes where human life as we know it is threatened.”

. . .

A century ago, exactly, the nation was also in a very bad way. In 1920 America had only recently emerged from a world war in which a mind-numbing 20 million people were killed, and that many also went home wounded. As it happens, the country was also recovering from a viral pandemic, the so-called Spanish flu, that killed off even more than the war — 50 million worldwide, 675,000 of them Americans. And while the gap between the haves and the have nots rocketed through the decade, culminating in the crash of 1929, even by 1920 the divide was greater than at any point between 1945 and 2000.

Poet William Butler Yeats wrote* in 1919:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

In this context, then, it is perhaps not surprising that in 1920 a little-known senator from Marion, Ohio was elected president. He vowed in his acceptance speech at the Republican convention, “We must stabilize and strive for normalcy, else the inevitable reaction will bring its train of sufferings, disappointments and reversals.” This was not particularly stirring rhetoric, nor was it striking otherwise — but for one thing: the nominee, Warren G. Harding, had effectively coined the term “normalcy” for that speech.

And people took notice.

The Tennessean newspaper wrote: “Candidate Harding startled some of his hearers when he used ‘normalcy’ in a sentence in his acceptance speech; some good Democrats shouted that there was no such word. A bold Republican editor in New York City turned to his dictionary, and not finding it there, proclaimed Harding a genius who invented his words to fit the occasion.”

The New York Evening World opined, “Candidates and partisans are prone to coin new words and phrases, to develop new meanings for words in common use. In the heat of the campaign these are fused into the language and become part of the national tongue. The present campaign is no exception. ‘Normalcy,’ which Candidate Harding used in his acceptance speech, is the best example so far.”

Before entering politics Harding had spent years as editor of the Marion Star, the town’s daily newspaper, and he well understood the power of a compelling turn of words. His use of the word “normalcy” generated such a buzz that Harding incorporated it into his campaign slogan: Return to Normalcy.

Though it took ten ballots at the deadlocked convention to nominate Harding, he won the general election in a landslide. People yearned for normalcy! But people also were captivated by the ingenious campaign appeal.

As a lifelong student and practitioner of advertising, I am fascinated by and have great respect for effective strategies and techniques of all sorts. Harding’s slogan reminds me of some other creative, and successful, ad campaigns predicated on improper grammar. Apple’s “Think Different” slogan was widely scorned for abusing the rules of good grammar, but it sure grabbed people’s attention. For similar reasons so did the headline, “Got milk?” My all-time favorite, though, as it’s the most discordant headline of the bunch, was the teaser ad for Alfred Hitchcock’s thriller, The Birds.

Over time the phrase “return to normalcy” entered common parlance. Coincidentally (or not) the term showed up in two emails I received over a recent 24-hour period.

. . .

So here we are, a hundred years after a small-town newspaper editor captured the national attention with a quirky campaign slogan. As before, we are in an election year — and once again, we are desperately seeking normalcy.

Sure, we want this horrible viral scourge to be gone. But beyond that, many of us want to see our general welfare elevated considerably, too. But to what normalcy, exactly, do we seek to return?

Aaron Sorkin, writing for his character Will McAvoy in The Newsroom, described a nobler America of not too long ago:

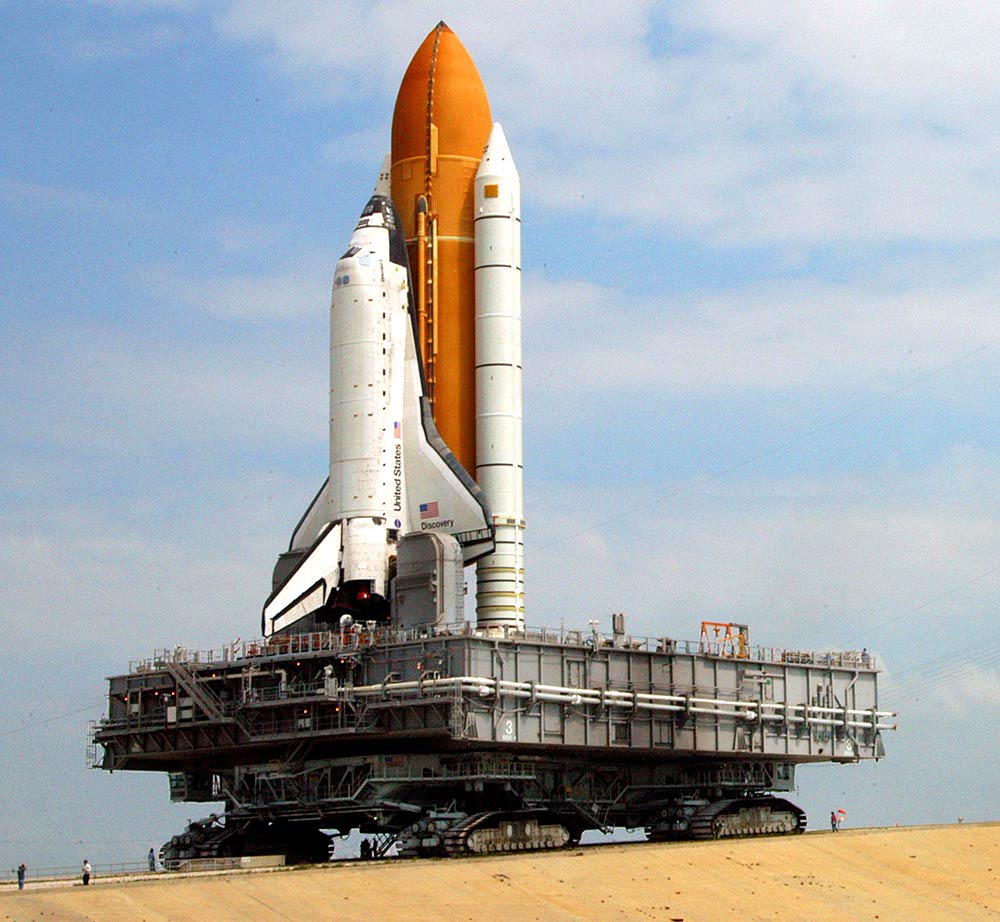

We stood up for what was right. We fought for moral reasons; we passed laws, struck down laws, for moral reasons. We waged wars on poverty, not on poor people. We sacrificed, we cared about our neighbors, we put our money where our mouths were and we never beat our chest. We built great, big things, made ungodly technological advances, explored the universe, cured diseases and we cultivated the world’s greatest artists and the world’s greatest economy. We reached for the stars, acted like men. We aspired to intelligence, we didn’t belittle it. It didn’t make us feel inferior. We didn’t identify ourselves by who we voted for in the last election — and we didn’t scare so easy. We were able to be all these things and do all these things because we were informed … by great men, men who were revered.

Sorkin pens some forceful, dramatic, television; the portrait McAvoy paints of America’s more glorious past sounds practically mythological.

And yet, I’m old enough to have tasted that flavor of normalcy. I witnessed a president rally the nation to visit the moon and within a decade, we’d achieved that dream. In the 1950s and ’60s Leonard Bernstein hosted 53 hour-long episodes of his “Young People’s Concerts,” using the New York Philharmonic to illustrate musical concepts. The series was broadcast by CBS on Sunday afternoons — and that, alongside groundbreaking shows like “I Love Lucy” and “The Twilight Zone,” was considered popular entertainment! Due to the GI Bill, historically progressive rates of taxation, and a booming post-war economy, America’s middle class flourished in those decades like never before, or since.

At least one “great, big thing” — one, even, that furthered our exploration of the universe — was borne of the engineering prowess and manufacturing might of Marion, Ohio: the crawler/transporter that carried each of the space shuttles from their immense hangar out to the launch pad at Cape Canaveral was built by the Marion Power Shovel Company.

Not all Americans, of course, especially those of color a half-century ago, experienced the same normal I did. Even so, from 1945 through the 1970s, the rising economic tide did lift all boats. Since around 1980, however, economic gains have been distributed less uniformly, and I believe it’s this growing disparity that undergirds much of the disillusionment, anger and despair we see, and feel, today.

So yes, by all means, let’s Return to Normalcy.

There are many consequential issues that will be debated over the next few months — and, no doubt, far beyond the election. But addressing two would, I think, go a long way to restoring some equilibrium to our civic, political and social lives.

As I said just above, I believe economic challenges are at the root of the distress felt in many segments of society. In a 2018 report, the Federal Reserve revealed that “four in 10 adults, if faced with an unexpected expense of $400, would either not be able to cover it or would cover it by selling something or borrowing money.” The current crisis is exposing vulnerabilities across a much broader swath of the population than most people could’ve imagined. I’d like to think that anyone willing to work hard for 40 hours a week could afford a roof over his head and enough to eat — and have at least $400 tucked away somewhere.

As important, I seek a normal in which a truly quality education is guaranteed for all. As Will McAvoy says, Americans can do great things only if they’re informed, and only if teachers and other smart people are revered.

American History and Civics should be required classes; regardless of our individual cultural heritage, all who are or aspire to be Americans must know our origin story, and learn of the Enlightenment principles that inspired our founders. They need to know how our systems of government and justice are meant to work. Plus, knowledge of and respect for our common cultural DNA might help us as a nation become less polarized — and, perhaps, less cynical; it’s hard not to be awed by the founders’ vision and exceptional achievement.

Students’ lives will be immeasurably richer with access to a full complement of classes in the arts. Humanity expresses itself most profoundly and eloquently through art, literature, music and theater — and humanity, need I state the obvious, is something we all share.

So, provided with the security of a decent income, and the tools of a good education, a person can afford to both entertain her dreams and to pursue them. It’s my dream that this might be our new and abiding Normalcy.

. . .

Addendum

I was born and raised in Warren G. Harding’s home town of Marion, Ohio.

I lived my first ten years a block from the Harding Home and Museum. I attended Harding High School, and had dinner a few times at the grand-by-Marion-standards Harding Hotel. Driving by the magnificent Harding Memorial was a common occurrence. In that environment, it never occurred to me — and more important, no adult ever mentioned to me — that our homeboy prexy was best known outside of Marion as America’s worst president. Over the years I did, of course, become aware of that broadly accepted belief.

A decade or so ago, however, I read a different, more nuanced, view. Harding biographer John Dean (briefly a Marion resident and later White House Counsel to Richard Nixon, another contender for the worst-president mantle) maintains that the 29th president was not a bad person or a particularly bad president, merely a bad manager — that his biggest failing was hiring bad people, most notably his Secretary of the Interior, Albert Fall, who was in fact responsible for the Teapot Dome scandal that forever tainted Harding’s legacy. Of course there was, also, his long-running and ultimately widely known extramarital affair with Nan Britton….

Harding left lots for historians to study and for Marionites to be both proud of and embarrassed by, but his gift to the vernacular is without a doubt a noteworthy aspect of his legacy!

*Excerpt from William Butler Yeats’ poem, The Second Coming (full text here).