George Harrison incants, “and my friends have lost their way.”

It happens, fog in L.A.

Cars happen here, too, by the millions. Most of them still generate exhaust, and those emissions, mixed with smoke from refineries and factories, trucks and container ships, and myriad other sources — added to the fog — produce a noxious haze. When the sun bakes that mix, we get smog.

Smog is not a good thing, on the whole, but it helps create some of the most dramatic light of any city in the world — light that is, according to author Lawrence Weschler in a 1998 New Yorker article titled “L.A. Glows,” “the defining character of the place — the soul of the place.” Weschler, a New Yorker born in L.A., elaborates, “That light: the late-afternoon light of Los Angeles — golden pink off the bay through the smog and onto the palm fronds. A light I’ve found myself pining for every day of the nearly two decades since I left Southern California.”

Countless artists, filmmakers and writers have been awed by the light here and have paid tribute in their work. Several friends of mine, in fact, have produced wonderful pieces that capture the magic of our light. Contemplating those artists’ works inspired me to gather their images, and seek out others, with the idea of compiling a book. The subject is certainly deserving.

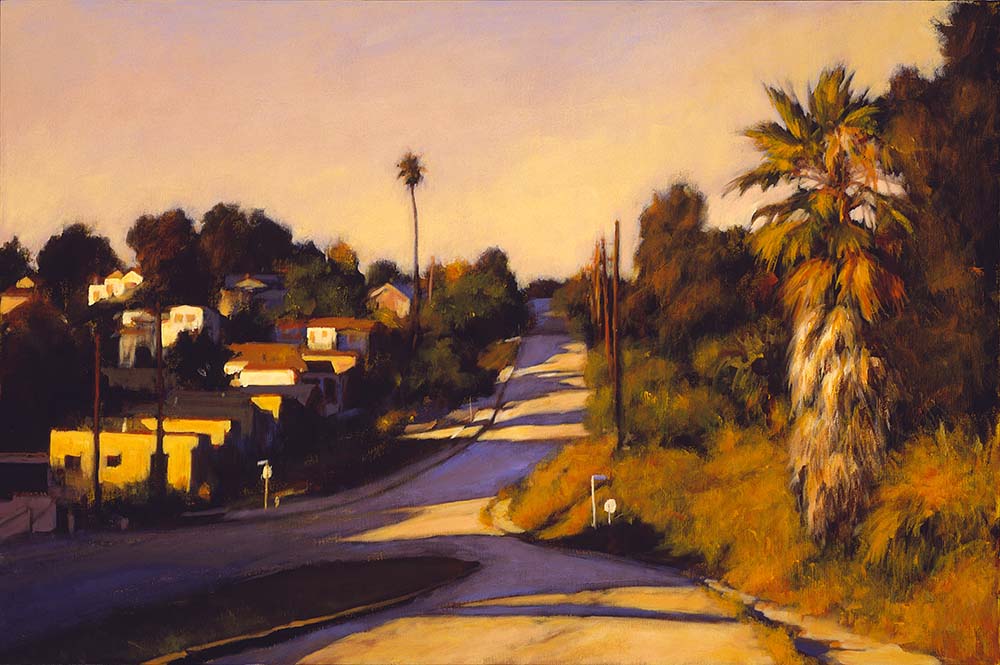

acrylic on canvas, c. 1997

(Click on images to enlarge.)

oil on panel, 8 x 24 in., 2006.

The artist writes: I may speak for others when I say that the quality of light is the highest ideal I have in mind when I’m painting. The houses and streets are the body of the work but the light is the soul.

I imagined a collection of paintings, prints and photographs that each represent some aspect of the light that graces our region. I’d want to intersperse those with textual passages referencing the subject; so many people of every stripe have waxed eloquently about the light here. Artist Robert Irwin:

One of its most common features … is the haze that fractures the light, scattering it in such a way that on many days the world almost has no shadows. Broad daylight — and, in fact, lots and lots of light — and no shadows. Really peculiar, almost dreamlike. … I love walking down the street when the light gets all reverberant, bouncing around like that, and everything’s just humming in your face.

Our smog is cooked according to a variety of recipes. Los Angeles sits at the western edge of the continent on a semi-arid plain, surrounded by mountains and the vast Mojave and Colorado deserts. It also sits at the eastern edge of the even more vast Pacific Ocean. Sometimes what particulate matter floats in the air is comprised primarily of water vapor, which makes for a diffuse, bright white light. And sometimes, during the dry hot months of late summer, it’s mostly dust and smoke (including from the occasional wildfire), producing a distinctive brownish haze — the light of which we euphemistically refer to as “golden.” As I said above, it’s virtually always a mixture of the two (smoke + fog = smog).

Local author and poet Don Waldie describes several distinct experiences:

There are four — or, anyway, at least four — lights in L.A. To begin with, there’s the cruel, actinic light of late July. Its glare cuts piteously through the general shabbiness of Los Angeles. Second comes the nostalgic, golden light of late October. It turns Los Angeles into El Dorado, a city of fool’s gold. It’s the light William Faulkner — in his story “Golden Land” — called “treacherous unbrightness.” It’s the light the tourists came for — the light, to be more specific, of unearned nostalgia. Third, there’s the gunmetal-gray light of the months between December and July. Summer in Los Angeles doesn’t begin until mid-July. In the months before, the light can be as monotonous as Seattle’s. Finally comes the light, clear as stone-dry champagne, after a full day of rain. Everything in this light is somehow simultaneously particularized and idealized: each perfect, specific, ideal little tract house, one beside the next. And that’s the light that breaks hearts in L.A.

The light here is more pronounced than in most big cities because few of us live amid tall buildings. The city is, famously, an expansive suburban sprawl; we see a lot of sky.

The artist notes: This photograph was taken near the infamous Florence and Normandie [intersection] where the 1992 LA Riots set off. I heard a car collision and turned around. This is the image that I saw and captured.

. . .

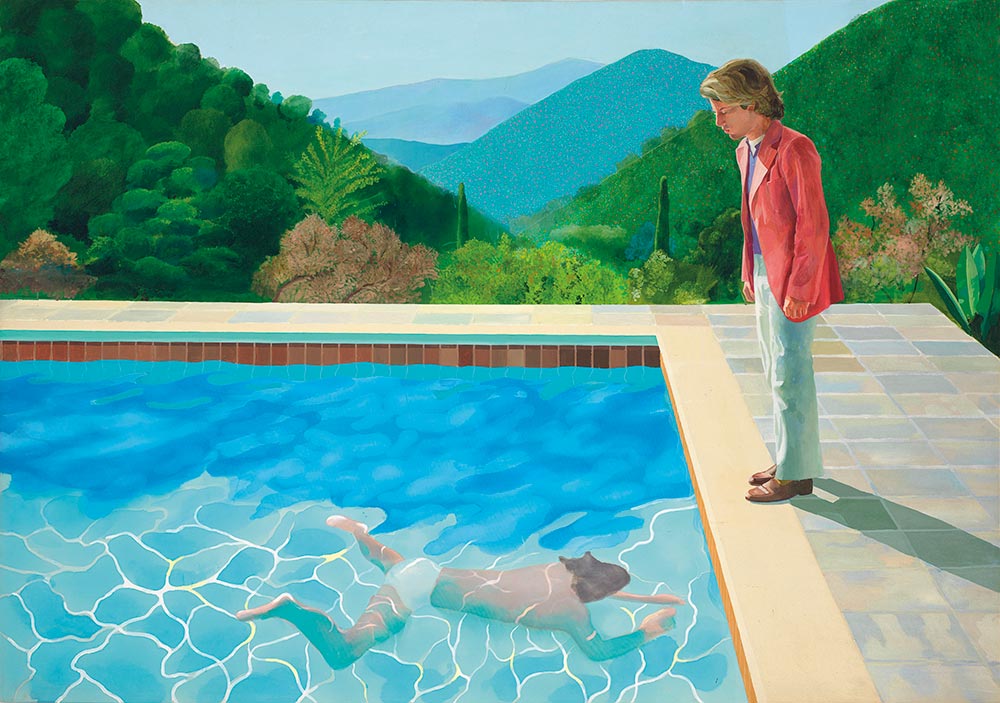

So, as I pursued this project, pieces by famous artists quickly came to mind. I learned David Hockney moved here in part because of the light.

As a child, growing up in Bradford, in the North of England, across the gothic gloom of those endless winters, I remember how my father used to take me along with him to see the Laurel and Hardy movies. And one of the things I noticed right away, long before I could even articulate it exactly, was how Stan and Ollie, bundled in their winter overcoats, were casting these wonderfully strong, crisp shadows. We never got shadows of any sort in winter. And already I knew that someday I wanted to settle in a place with winter shadows like that.

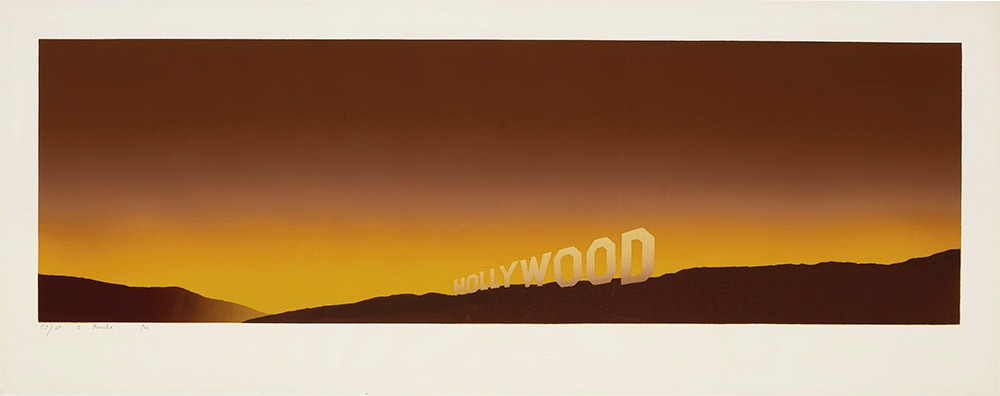

image: 12 1/2 × 40 7/8 in., 1968

Additionally, I’ve discovered quite a few artists I hadn’t known of who’ve effectively conveyed the experience of our ambient light in their works.

I suffer from the blessing, and the curse, of having more ideas and ambitions than I have the ability and the time to realize. So after my initial explorations, this idea joined many others on the proverbial back burner.

. . .

Nearly a decade passes, and I come upon a lyrical passage in a piece by Los Angeles Times columnist Chris Erskine:

While coffeeing the other morning, I started to marvel at the sun. Yeah, that sun, the one that lights the sky every day. Big deal, right? I mean, really. The sun?

Yet after careful contemplation I came to the rather unoriginal conclusion that Los Angeles is the Land of Light, just as Paris is the City of Lights or Chicago is the Windy City.

I suddenly got all philosophical about the California sun, how it burnishes the coastline, tints our foreheads. Perhaps no other city is so defined by sunlight. In L.A., sun is our soul point. Sun makes us smile, even as it threatens to fry our future.

These few lines, in a column about befriending a stranger in a coffee shop, brought my project back to mind. Erskine even gave it a title — Los Angeles: Land of Light. I gathered more images and wrote a short treatise of my intent, but then, alas, it slid back down my list of priorities.

Erskine’s column appeared four years ago. In the time since, nothing more happened with my notion. Then, within the past few weeks, two things occurred: Chris announced his retirement from the paper, which somehow jogged my memory of the book idea; and, restrictions imposed during the coronavirus lockdown altered my work and life patterns sufficiently to allow time to revisit the project, and to craft this story.

Digging back into it this time, I discovered Lawrence Weschler’s New Yorker article, cited above, that contains marvelous observations by artists, poets, scientists, filmmakers, and other writers, several of which I’ve excerpted here. Weschler even spoke with legendary LA Dodger announcer Vin Scully:

Come late July, with the sun setting off third base, the air actually turns purple tinged with gold, an awesome sight to behold, the Master Painter at work once again, and, owing to the orientation of the stadium, out beyond center field, you’re staring at the mountains, and mountains beyond mountains, indeed the purple mountains’ majesty spread out there for everyone to see.

And on evenings like that it can get to be like a Frederic Remington or a Charles Russell painting, the dust billowing up from the passing cars on the freeway. If you squint your eyes and only let your imagination soar, it’s as if a herd of wild horses were kicking by.

In the late afternoon of November 16, 1976, a singular UFO-shaped cloud appeared above Hollywood. New West magazine published a poster of twelve of the many photographs people shot that day, including this one and images by David Hockney, Paul Ruscha, Ros Cross, Dennis Worden and Mick Haggerty.

. . .

The air in Los Angeles has greatly improved since I came here in 1970. As a student at Art Center I first lived in a boarding house not three miles from the Hollywood Hills, but most days I couldn’t even tell they were there. In these recent months of “sheltering in place,” during which many fewer drivers were on the roads, and especially following several cleansing rains, the air has been pristine. From the proper vantage in the Verdugo Mountains near my home, the profile of Santa Catalina Island 60 miles away is clear and crisp.

And yet, this is Los Angeles. People drive, refineries refine and the imposing Santa Monica and San Gabriel Mountains north and east of the basin trap the air, preventing what fumes we generate from leaving easily. Consequently, for good and for ill, the city is likely to be a land of extraordinary light for a very long time.