I struggled after the 2016 election to understand how enough of us could vote for Donald Trump to make him president. From the outset he struck me as a con — a “snake-oil salesman,” many called him — and I’ve struggled since to understand his continued appeal to a sizable segment of the population.

Throughout his first campaign Trump demonstrated himself to be unfit for office. Right out of the chute, in a speech launching his candidacy, he condemned immigrants from our neighbor to the South: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. … They’re sending people that have lots of problems … They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” In the following months he mocked a disabled journalist, denigrated Senator John McCain for having been captured in Vietnam, boasted of grabbing women by the pussy, and more.

So when he won, I was gobsmacked.

To wrap my head around this seeming impossibility, this travesty, I read a ton. A handful of factors contributing to Trump’s victory ultimately came to light: an opponent, an outspoken female, who was as disliked as Trump; widespread distrust of established politicians — and as the spouse of a former president and a former Secretary of State and Senator herself, Hillary Clinton was the quintessential establishment candidate; then-recent rulings by the Supreme Court that enable wealthy donors to contribute unlimited amounts of money to fund candidates and officeholders, thus helping to sway elections in a Republican direction; and not least, Russian-produced propaganda favoring Trump flooded social media in surgically targeted districts.

Given the narrow vote margins in just a few pivotal states, any one of these factors could have tipped the scales for Trump. But there was more.

Key to Trump’s appeal to blue-collar workers in the Midwest, where he edged out Hillary Clinton in several states, was an economy that over four or five decades had disenfranchised the middle class, causing millions to feel irreconcilably disheartened, afraid and angry. I was born and raised in a small Midwestern town, and worked two summers in a steel mill; I witnessed the Rust Belt rust firsthand.

Barack Obama made this observation at a 2008 fundraiser:

You go into these small towns in … the Midwest, the jobs have been gone now for 25 years and nothing’s replaced them. And they fell through the Clinton administration, and the Bush administration, and each successive administration has said that somehow these communities are gonna regenerate, and they have not. And it’s not surprising then they get bitter, and they cling to guns or religion or antipathy toward people who aren’t like them or anti-immigrant sentiment or anti-trade sentiment as a way to explain their frustrations.

Hillary Clinton eight years later wasn’t nearly as diplomatic. Speaking at a fundraiser less than two months before election day, she said this:

You know, to just be grossly generalistic, you could put half of Trump’s supporters into what I call the basket of deplorables. Right? The racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamaphobic—you name it. And unfortunately there are people like that. And he has lifted them up.

Few remember the comments following that incendiary description of half of Trump’s supporters, but Clinton observed that the other half “feel that the government has let them down” and are “desperate for change. … Those are people we have to understand and empathize with as well.”

I can’t abide calling millions of Americans deplorables, but there’s no denying the xenophobia, racism and sexism — intolerance generally — that’s become more acceptable since Trump’s first run for office.

So, I get how Trump’s racist and anti-immigrant proclamations resonate with far too many Americans, but I still can’t grok how so many of modest means identify Donald Trump, a self-proclaimed billionaire New York real estate tycoon, as a champion of their interests. Days after the election, I addressed that idea in my Facebook header image.

Some time later I read an explanation that, as cynical as it sounds, rings true: Donald Trump is a poor man’s idea of a rich man, a weak man’s idea of a strong man, and a stupid man’s idea of a smart man. A characterization of Trump devotees that also made sense to me is that they are akin to cult members — wholly, irrationally and immutably enthralled with, and yoked to, their leader.

Which makes me think: while I’ve been focused on Donald Trump, where we are now as a nation might be better understood by looking at the Americans to whom he appeals.

. . .

Numerous polls have revealed how ill-informed so many Americans are about the way their government functions. The Annenberg Public Policy Center found that more than a third of those surveyed can’t name any of the rights guaranteed under the First Amendment, and only a quarter of Americans can name all three branches of government. Ouch!

However little Americans know about their government, they nonetheless disapprove of it, and strongly: fewer than two in ten say they trust the government in Washington to do what is right “just about always” (1%) or “most of the time” (15%).

Government is the easiest target of suspicion and derision, but most institutions have suffered similarly in the public eye.

Regarding the one historically responsible for keeping us citizens informed, a mere 32% of Americans say they trust the mass media “a great deal” or “a fair amount” to report the news in a thorough, fair and accurate way. Another 29% of U.S. adults have “not very much” trust, while a record-high 39% register “none at all.” Double ouch.

Stunningly, but not surprisingly, a 2022 YouGov poll found a significant partisan divide in this area, the widest by far of any industry: Democrats had a 17% favorable rating of News Media, while Republicans had a 57% unfavorable rating.

The breakdown of trust in government, institutions generally, and news media specifically, is bad news for democracy, and good news to those who wish us harm.

In early 2017, Masha Gessen wrote in the New York Times, “Fascists the world over have gained popularity by calling forth the idea that the world is rotten to the core. In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt described how fascism invites people to ‘throw off the mask of hypocrisy’ and adopt the worldview that there is no right and wrong, only winners and losers. … Autocrats like Vladimir V. Putin and Viktor Orbán have adopted this cynical posture. They seem convinced that the entire world is driven solely by greed and hunger for power, and only the Western democracies continue to insist, hypocritically, that their politics are based on values and principles.”

Over the past several years many others have warned us about authoritarianism in this country and across the globe. Timothy Snyder’s modest tome, On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century; former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright’s Facism: A Warning; Rachel Maddow’s Prequel: An American Fight Against Fascism; and Masha Gessen’s own Surviving Autocracy, are four of dozens of books published just since Trump was inaugurated. And, through documentaries such as “Nazitown U.S.A.” and Ken Burns’ series, “The U.S. and The Holocaust,” even PBS is ringing the alarm, drawing parallels between the 1930s, when many in the United States supported Nazi Germany, and now.

The threat is undeniable, and it behooves us to recognize how fascists operate and to resist those trends whenever, wherever and however possible. My focus here, though, is on the root causes of our predicament, and ways to make things better. I’ve identified several over the past few years, but have come to believe that the health of our democracy could be most effectively improved by respecting and funding education, specifically education in civics, government and history. Civics education, taught well, can equip and inspire students to become informed and engaged citizens.

Presidential historian Michael Beschloss wrote:

If our schools won’t teach American civics and democracy, our population will feel increasingly indifferent or even hostile towards the system that is supposed to protect our freedoms.

Professor of Education at UCLA, Maryanne Wolf, concurs:

The great, insufficiently discussed danger to a democracy stems not from the expression of different views but from the failure to ensure that all citizens are educated to use their full intellectual powers in forming those views. The vacuum that occurs when this is not realized leads ineluctably to a vulnerability to demagoguery, where falsely raised hopes and falsely raised fears trump reason and the capacity for reflective thinking recedes, along with its influence on rational, empathic decision making.

And Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Will Bunch goes further:

You can draw a straight line between the country’s collective decision — hardened somewhere in the late 20th century — to stop seeing education as a public good aimed at creating engaged and informed citizens but instead a pipeline for the worker drones of capitalism, and the 21st century’s civic meltdown that reached its low point … in the Jan. 6 insurrection.

That’s quite an indictment, but consider: If people better understood the Constitution and valued its fundamental premise, the separation and balance of powers, they would instinctively be wary of a candidate who, in accepting his party’s nomination for president, declares the nation to be in crisis, enumerates several dangers, then proclaims, “I am your voice. I alone can fix it. I will restore law and order.” As Yoni Applebaum in The Atlantic pointed out, Trump “did not appeal to prayer, or to God. He did not ask Americans to measure him against their values, or to hold him responsible for living up to them. He did not ask for their help. He asked them to place their faith in him.” Such authoritarian expressions by a major-party nominee for president are unprecedented in this country.

If enough Americans understood and embraced the First Amendment to the Constitution, the hair on the backs of their necks would bristle when a candidate — and then a president — openly disparages journalists covering his campaign speeches, dismisses news articles containing comments critical of him as “fake news,” or most egregiously, flat-out refers to the press as “the enemy of the people.”

Also in the First Amendment is protection of our right to practice any religion — or no religion — yet Donald Trump has made evident his antipathy for Islam and its Muslim adherents. Current Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson has proclaimed that America is and was founded as a Christian nation. More on the right are proclaiming that there should be no separation between church and state, the Bill of Rights be damned.

. . .

I view Civics as our secular religion. The founders structured our government based on values and principles, among them that the rule of law is paramount, and we the people are sovereign — not a king, and not an elected president. Assurances were built into the Constitution, the blueprint of the edifice the framers envisioned, to protect against any individual, or government entity, from becoming too powerful. And to Hannah Arendt’s point, the rule of law affirms and defines what is right and wrong.

Thanks to Donald Trump, primarily, we’re learning a harsh lesson: that people who swear an oath to the Constitution can nonetheless violate its doctrine, sometimes with impunity. And, that our institutions cannot sustain themselves — their integrity, even their survival, relies on our belief in our system of government, and our collective efforts to uphold it.

When an official at the highest level of one branch of government disregards a subpoena from another branch, checks and balances and separation of powers, two of the bedrock principles undergirding the founders’ vision, prove vulnerable. Likewise, when high government officials, including the president, publicly attack individual election workers, or when partisan extremists harass poll workers — most of whom are volunteers — or the state officials who oversee elections, it causes every election worker, from secretaries of state on down, to feel at risk.

Donald Trump has long cast into doubt our ability to trust the results of our elections. Even after he won in 2016, he claimed — without any proof, of course — “I won the popular vote if you deduct the millions of people who voted illegally.” During his 2020 campaign Trump spewed allegations of fraud, warning as early as August 2020 that “the only way we’re going to lose this election is if the election is rigged.” And since the election, he’s propagated the “big lie,” that the 2020 election was stolen from him. Tragically, millions believe this still — and shockingly, many Republican members of congress won’t publicly affirm Joe Biden’s victory.

To sew distrust in the fundamental principle of a democracy — that every citizen has a voice, and that his vote will count — is to take aim at the entire system.

As I write this, Donald Trump is on the verge of becoming the Republican Party nominee for president, again. Through countless actions and statements — things he did as president and things he’s done since, and things he’s promised to do and things others have promised to do were he to be elected — he represents the biggest threat to democracy, here and abroad, in my lifetime, and arguably decades longer. If that sounds hyperbolic, consider this: Angry at a decision Twitter made during the 2020 campaign, Trump wrote on his social media platform, “A Massive Fraud of this type and magnitude allows for the termination of all rules, regulations, and articles, even those found in the Constitution.”

On his own he would be no threat, of course, but millions of Americans support him, many fervently — and it’s my suspicion that quite a few of those supporters don’t sufficiently appreciate, or even understand, our system well enough to know how their chosen leader might trample over the freedoms and rights they themselves take for granted, and how he might damage the country otherwise. Exhibit A: January 6, 2021.

. . .

So how did we get here?

In the late 1960s and early ’70s, I was able to pay for my college education through summer jobs, a bit of savings, and modest help from my parents. In California, my adopted home, it was even easier — the University of California was tuition-free, at least until Ronald Reagan was elected governor and slashed state funding for higher education by 20 percent. When asked why he was doing away with free college, Reagan said that the role of the state “should not be to subsidize intellectual curiosity.” He maintained that position, promising during his presidential election campaign in 1980 to eliminate the Department of Education; then, once president, he appointed William Bennett, who had written extensively in support of that idea, to be secretary of education.

Budget cuts, plus increased focus on math and reading in K-12 education over the past couple decades has pushed out civics and other important subjects (such as art and music). Now, only seven states require a full year of civics instruction in high school; 13 states have no requirement at all.

And recently, battles in several states over what students can, or must, learn have raged, and hundreds of books in classrooms and libraries across the nation have been subject to bans.

. . .

The government of the United States did not spring wholly from the imaginations of our founders. Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, among others, were students of Enlightenment philosophers such as John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who wrote in the 17th and 18th centuries about individual rights, representative government and the social contract, bold ideas in a time when monarchs reigned across Europe and the Roman Catholic Church influenced all facets of life.

Enlightenment thinkers and writers promoted ideals such as liberty, progress, tolerance, constitutional government and democracy. Perhaps most important, they valued reason as the primary source of authority and legitimacy, and deemed science to be the preferred method of determining what is true.

At this moment, and as with most other institutions, science and its pursuit of truth is respected by too few Americans. Overall, only 57% of us say that science has had a mostly positive effect on society — and this share is down a whopping 16 points since before the start of the coronavirus outbreak.

There is a story, often told these days, that upon exiting the Constitutional Convention Benjamin Franklin was approached by a group of citizens asking what sort of government the delegates had created. His answer was: “A republic, if you can keep it.” Democratic republics are not merely founded upon the consent of the people, they also are absolutely dependent upon the continued active and informed involvement of the people for their good health.

The thought that ideas and ideals could be codified into law, and that laws, not men, represent a nation’s supreme authority, was radical in its day. The idea that a government can reflect the fluid will of its citizens while the principles on which it was established remain fixed, is genius – and America has exemplified how those principles might be manifest. To be born an American, and participate in this grand experiment in self-governance, is a blessing, and no effort should be spared, especially in these perilous times, to keep our republic.

Thomas Jefferson said, “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.” Jefferson was a champion of education, founding the University of Virginia and mandating that it be tuition-free. He believed that, “Whenever the people are well informed, they can be trusted with their own government; that whenever things get so far wrong as to attract their notice, they may be relied on to set them to rights.”

A person will not defend something he doesn’t care about, or even understand. I believe that civics education is the key to restoring our knowledge of government, and appreciation for the good it does for its people. The Constitution and the principles underlying it is the one thing every individual in this diverse nation has in common with everyone else. A sufficiently informed and involved citizen will identify threats to his nation and rise to defend it, if only with his vote.

. . .

Enlightenment has another meaning, of course, simply to gain knowledge, and to further one’s understanding of what’s true in his life and in his world. Enlightenment, Mr. Reagan, is the likely result of one’s indulging his intellectual curiosity, and that’s a beautiful thing.

To be clear, the regrettable state of education in this country predates Ronald Reagan. In 1980 Isaac Asimov wrote in Newsweek magazine, “There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there always has been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that ‘my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.’”

I read recently that 130 million Americans — 54% of adults between the ages of 16 and 74 years old — lack proficiency in literacy, essentially reading below the equivalent of a sixth-grade level. Can these people be trusted with their own government, in Jefferson’s words, or in Franklin’s, to keep their republic? I fear not, yet many nevertheless vote.

. . . . . . .

Back in 2017, when I determined for myself that education is the crucial fulcrum by which we can elevate ourselves out of these challenging circumstances, I secured the web domain, enlighten.us, with the idea of promoting education, and civics education in particular. It seemed imperative for me to learn more about our nation’s historical philosophical roots, and report what I discovered there. My goal was to add to the chorus of voices promoting civics education* and amplify them — to serve as another tiny beacon in a roiling sea. The first (and much shorter!) draft of this essay, intended to be the initial publication on my site, was written in 2018. Precious little has been done to further that project since, but along with many other ambitions I harbor, it has remained a dream, and inspired this update.

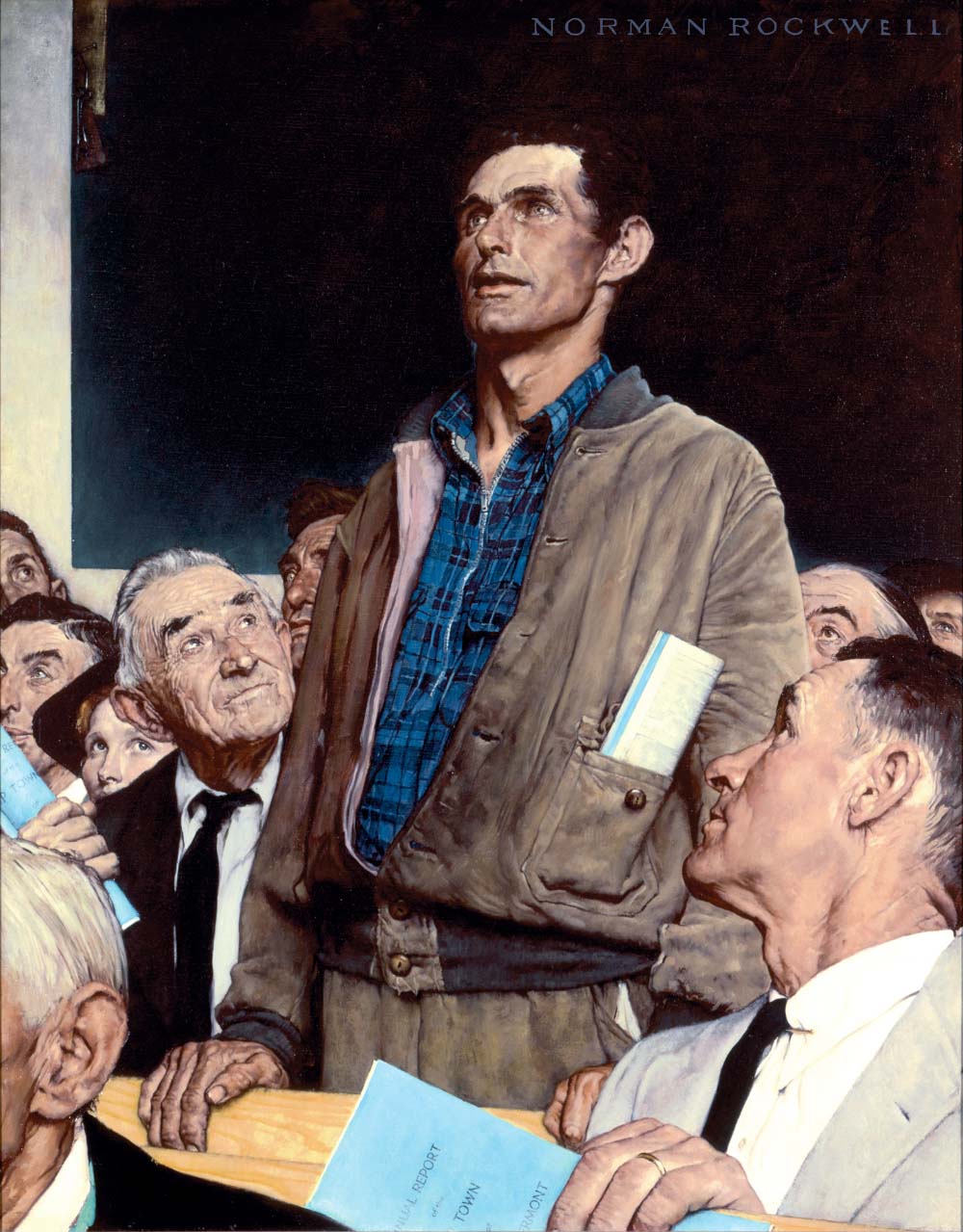

I take inspiration from Rockwell’s magnificent “Freedom of Speech” piece. Through making and sharing graphics such as several shown above, creating the “This/Not This” campaign with Dave Hackel over the past two election cycles, writing occasional letters to the Los Angeles Times, and not least, updating and publishing this essay, I am exercising my freedom of speech, and attempting to be a good citizen.

If you’ve read this far and would like to share your thoughts, I’d be interested to hear from you.

Additional Information

*Here are pages on two different web sites that list organizations dedicated to civics education — CivicsLearning.org and CivicEd.org.

I’ll highlight one of those organizations: the American Bar Association, no less, has referred to Civics as a “national security imperative.”

And just for fun, here are the 100 questions someone looking to be naturalized, i.e. to become a citizen, will be asked.